“I was captured for life by chemistry and by crystals.”

Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin

(Egypt, 12 May 1910 – United Kingdom, 29 July 1994)

“Oxford housewife wins Nobel”. That was the headline in certain British newspapers when Dorothy Hodgkin won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1964.

Hodgkin revolutionised the field of X-ray crystallography, by using this technique to study the three-dimensional structure of proteins. As a result, she discovered the crystal structure of insulin and also of penicillin and vitamin B12. But her achievements resonated beyond their practical applications, pushing the boundaries of scientific knowledge.

The power of x-rays

Our protagonist was born in Cairo in 1910, when Egypt was still a British colony. Both her father and mother had a keen interest in archaeology, a passion they passed on to their daughter, which gave her the opportunity to discover and analyse many minerals. The whole family spent winters in Africa and summers in England. When World War I broke out Dorothy Hodgkin and her sisters were forced to move to the UK when she was only four years old.

At 10, she met Dr. A. F. Joseph, a family friend, who sparked her interest in minerals and crystals by giving her a gift of analytical equipment. Her mother also played an important role in igniting her passion by giving her a book by Sir William Henry Bragg called “Concerning the Nature of Things” (1925). This book discussed how X-rays could be used to see atoms and molecules.

In England she attended Sir John Leman’s primary school in Beccles, where she struggled to attend a chemistry class that was traditionally reserved for boys (she was one of only two girls). She would later begin studying chemistry at Somerville College in Oxford where she would meet very few women along the way. Their participation was also very restricted. For example, they could not enter the dining hall unless accompanied by a male student.

During her first year she combined chemistry and archaeology. Fascinated by this field, after graduation she joined John Desmond Bernal’s laboratory for a PhD at Cambridge University. Bernal was a charismatic and progressive man, and in his lab women and men worked as equals.

She returned to Oxford in 1934, where she spent the rest of her long scientific career. Around this time she met Thomas Hodgkin, whom she would marry in 1937 and have three children. Although she was offered a career break, she continued her research and was the first person in academia to receive paid maternity leave, years before this was introduced in the UK.

Shortly after the birth of her first child, she was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, a progressive joint disease. Despite the suffering, she never let it get in the way of her research.

The queen of structures

Until that time, X-ray crystallography was only used to study mineral or inorganic crystalline structures. It was Bernal’s idea that the technique could also be used to understand biomolecules. But Hodgkin painstakingly established the parameters that made its use possible, laying the foundations for protein crystallography and structural biology. Her imaginative mind with a skill for understanding the patterns around her gave her a unique sensitivity for computing information from X-ray data. It took her 4 years to confirm the structure of penicillin (which facilitated the manufacture of this miracle drug) and 8 years to confirm the structure of vitamin B12. Finally, she resumed her work on insulin, which, with its 788 atoms, took the longest, but after 34 years of hard work she cracked the structure in 1969! Which she describes as one of the happiest moments of her life.

In 1964 she became the third woman to receive the Nobel Prize in Chemistry (after Marie Skłodowska-Curie and her daughter, Irene Joliot-Curie) for her achievements, which not only solved some mysteries but also helped to tackle diseases such as diabetes, anaemia and infections. For these discoveries, she was also elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of London and awarded the Order of Merit by Queen Elizabeth II of England.

Ambassador for peace

Hodgkin was also a strong advocate of nuclear disarmament and fought for the cause as chair of the Pugwash Conference (a global organisation working to reduce armed conflict). She donated most of her Nobel Prize money to causes such as scholarships for international students in the UK and the establishment of nurseries for university students and staff.

Hodgkin left us in 1994, aged 84, after suffering a heart attack. But what will always live on are her discoveries, which had a huge impact on the health and lives of millions of people.

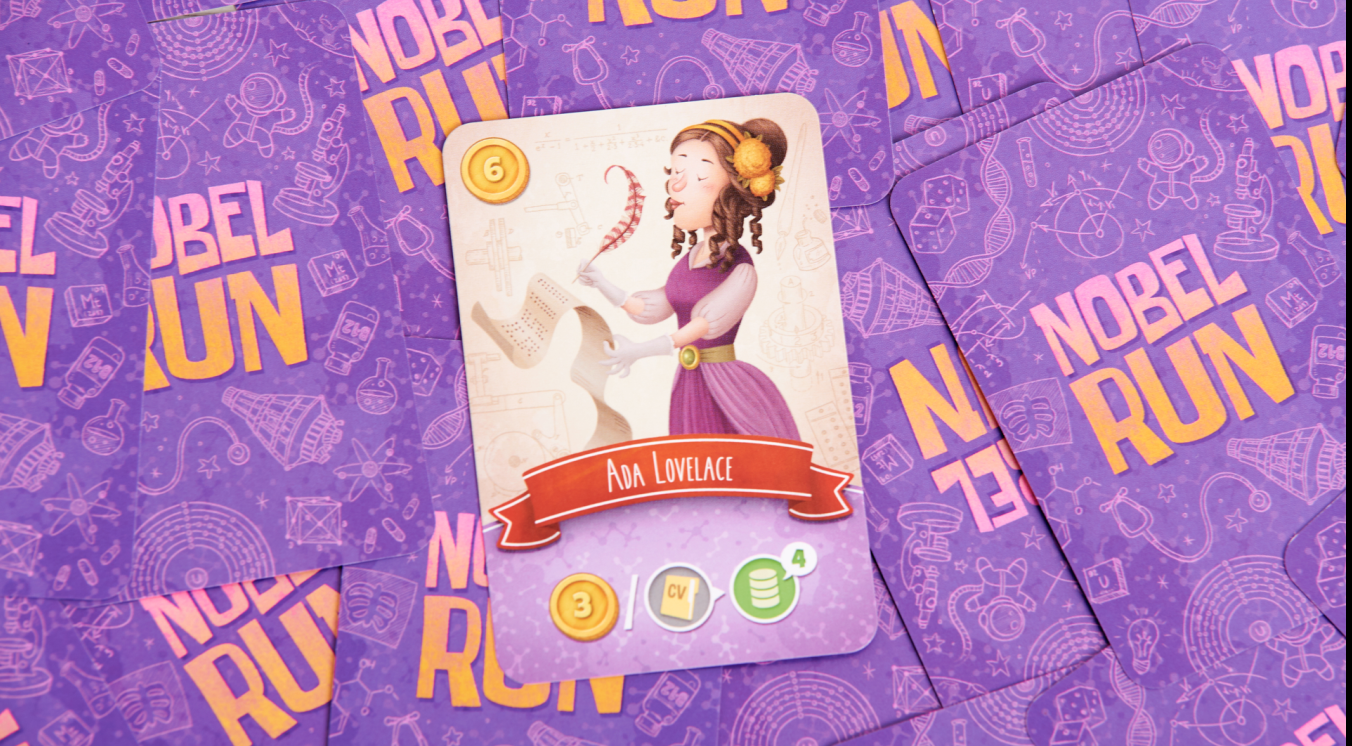

Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin is one of the scientists who appears in our board game Nobel Run. More info: Gearing Roles launches the Nobel Run board game to give visibility to women in science.

Text by Lorena Fernández (@loretahur).

Illustrations by Iñigo Maestro (@iMaestroArt).